Multifocal

ERG/VEP M-sequence

(Maximal sequence)

Ai-Hou

Wang, M.D., Ph.D.

During

my year-long Fellowship of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus at The

Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute (SKERI) in San Francisco from the

summer of 1990 to the summer of 1991, I had the opportunity to work with two

electrophysiological designs: Dr. Erich Sutter's

multifocal electroretinography (ERG) and Dr. Anthony Norcia

and Dr. Christopher

Tyler's sweep visual evoked potentials (Sweep VEP). Currently, the

International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) has

standards for multifocal ERG (https://iscev.wildapricot.org/standards),

but standards for sweep VEP have not yet been included. Besides clinical use,

these two tools are also invaluable for basic scientific research in vision.

Using

images to elicit electrical responses in the retina and visual cortex is called

pattern ERG and pattern VEP. The most commonly used

image is a checkerboard reversal (left image).

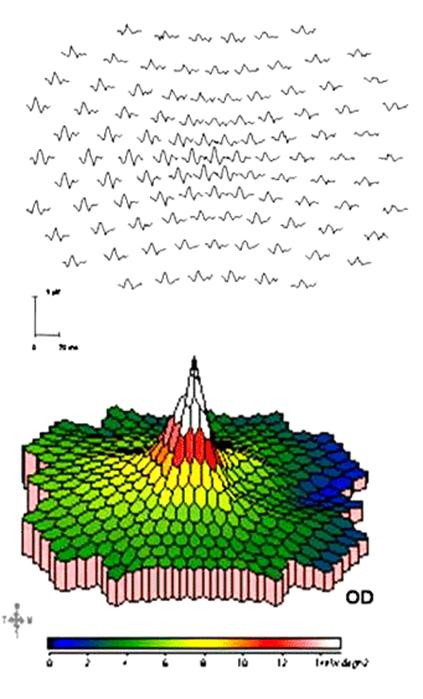

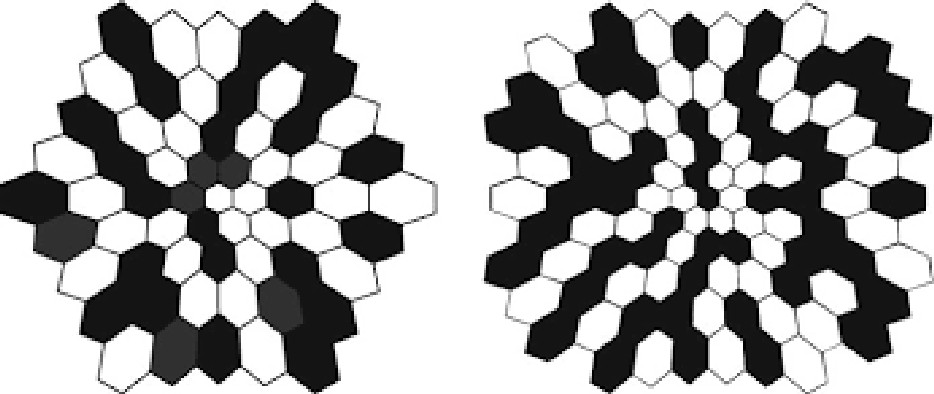

Multifocal

ERG and multifocal VEP use the pattern shown in the right figure as the visual

stimulator.

The

method of recording multifocal ERG is similar to that

of pattern ERG (left figure), using the screen image as the visual stimulator

while keeping a constant average screen brightness. Its

records the electric response to each small hexagon (right figure). Locally, it

however appears similar to flash ERG.

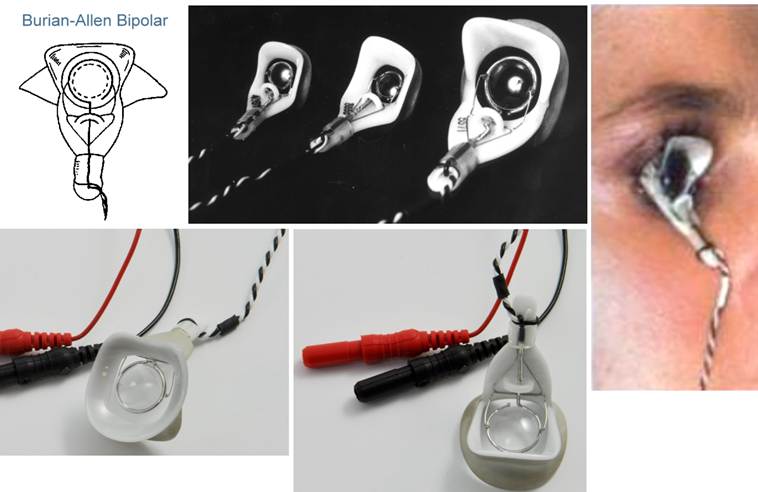

The

electrodes used to record multifocal ERG are no different from those used in

ordinary ERG (see figure). So many hexagons are flashing simultaneously,

stimulating every local retinal area. How is it possible to analyze and record

so many individual retinal responses? The calculation is a sophisticated 0-1

mathematical approach called the maximum sequence (M-sequence).

This article will explain the calculation of

M-sequence and introduce our alternative method and findings in recording

binocular VEP with M-sequence.

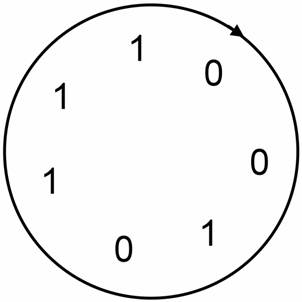

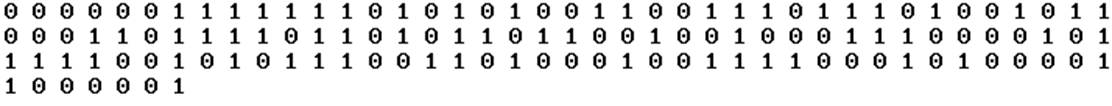

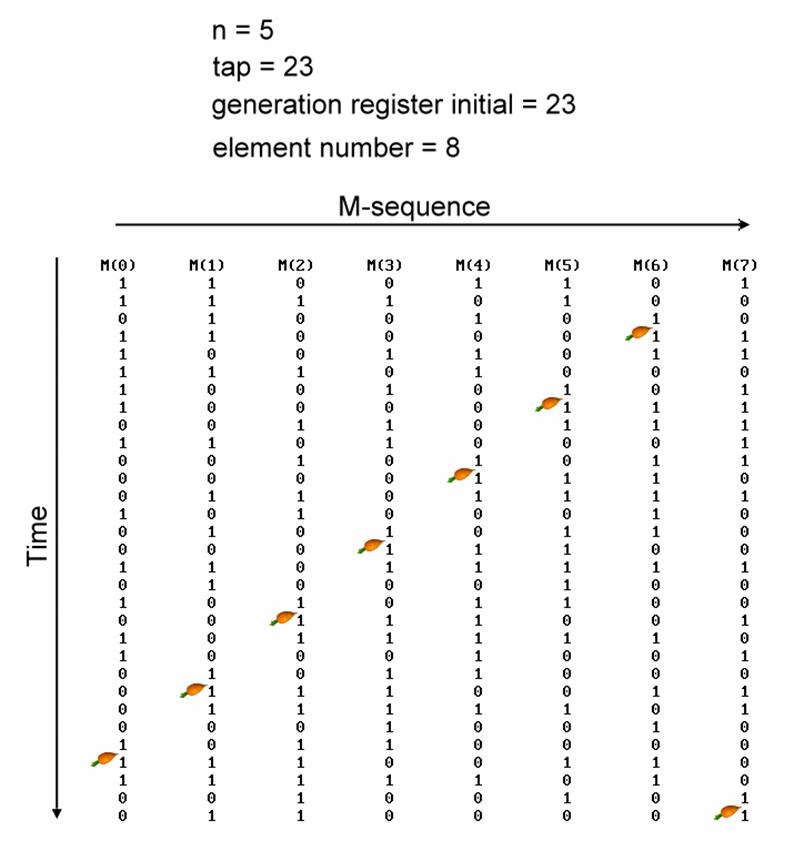

The M-sequence,

also known as pseudorandom M-sequence, is a sequence of 0��s and 1��s (see

figure). While it appears to be a random arrangement of 0��s and 1��s, the

generation of this sequence follows a formula and is not truly random; hence the name pseudorandom sequence. In

psychophysical or physiological experiments, the appearance of 0��s and 1��s is

essentially random and unpredictable.

The

length of M-sequence (the total number of 0��s and 1��s) is 2n-1 0��s

and 1��s for a given integer n. The sequence contains 2n-1 1��s and 2

n-1 - 1 0��s, with one more 1 than 0.

The

M-sequence of n = 3 has 23 - 1 = 7 0��s and 1��s.

[

1 0 0 1 0 1 1 ]

It is a loop; you can start from any position of the

loop. There are 7 M-sequences.

The M-sequence of n = 7 has 27 - 1 = 127 0��s and 1��s.

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1

1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1

0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0

0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1

1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 [0 0 0 0 1]

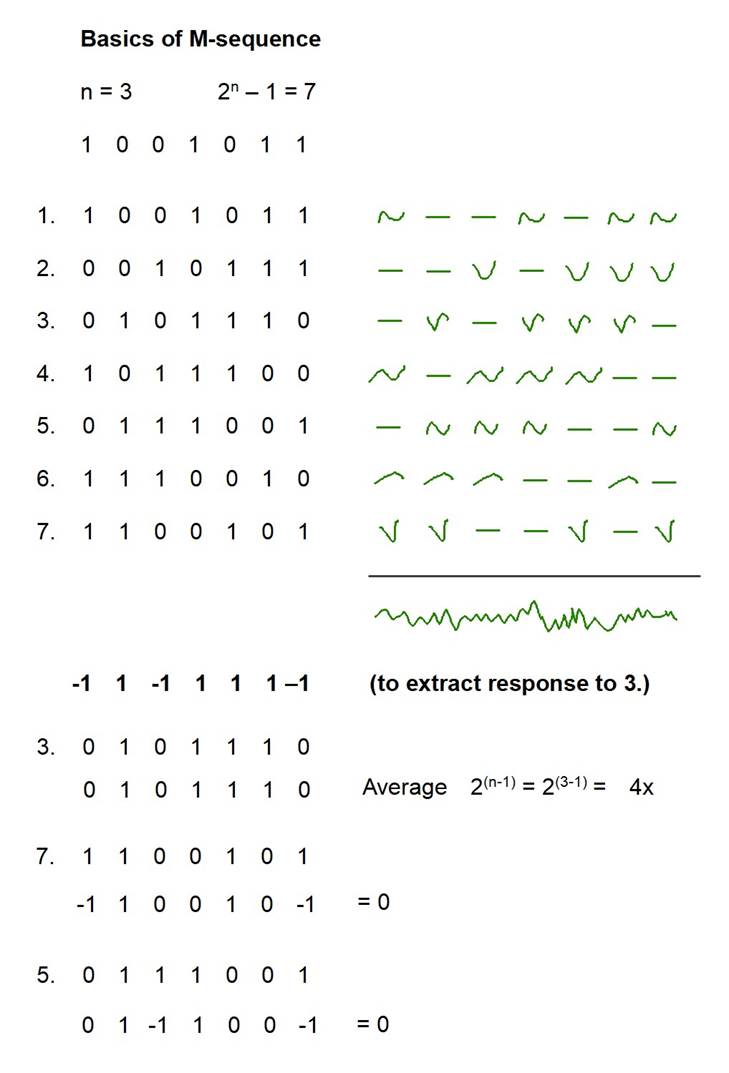

Let's first look at the secret of how the M-sequence can

analyze and record so many individual retinal responses �V

As mentioned before, there are 7 M-sequences with n = 3.

A stimulus is input according to each sequence �V if it��s 1 in the sequence, a

stimulus is given, and a response is obtained; if it��s 0 in the sequence, no

stimulus is given, and no response is obtained (see figure). 7 stimuli are

input simultaneously according to these 7 M-sequences, and the 7 responses are

summed together to give the output.

We multiply the summed responses by [-1 1 -1 1 1 1 -1]

according to the third M-sequence [0 1 0 1 1 1 0]. We subtract when it��s 0 in

the sequence and add when it��s 1 in the sequence. The calculation result for

the 3rd input is a sum of 2(3-1) = 4 times. The calculation result

for the 5th input is to add twice and to subtract twice, that cancel out each

other to get 0 result; the calculation result for the 7th input is also to add

twice and to subtract twice, canceling out to get 0 result. Except for the response

from the third sequence stimulus, which is summed four times, the responses

from the other six sequences are cancelled out by themself and do not appear in

the calculation result. Therefore, the response from the third sequence

stimulus can be extracted from the summed responses. Similarly, by adding and

subtracting the summed responses based on the 0��s and 1��s of the other six

sequences, we would be able to obtain individual response from each sequence

stimulus.

Thus, the M-sequence is a multiple-input, single-output system.

By utilizing the characteristics of M-sequence, the individual response from

each input can be separated from the single output.

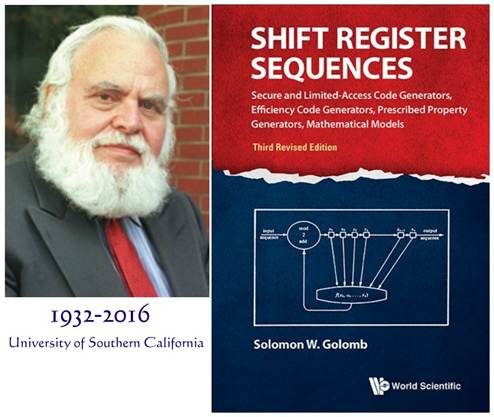

About

this magical mathematics of 0 and 1, please refer to ��Shift Register Sequences��

by Solomon W. Golomb

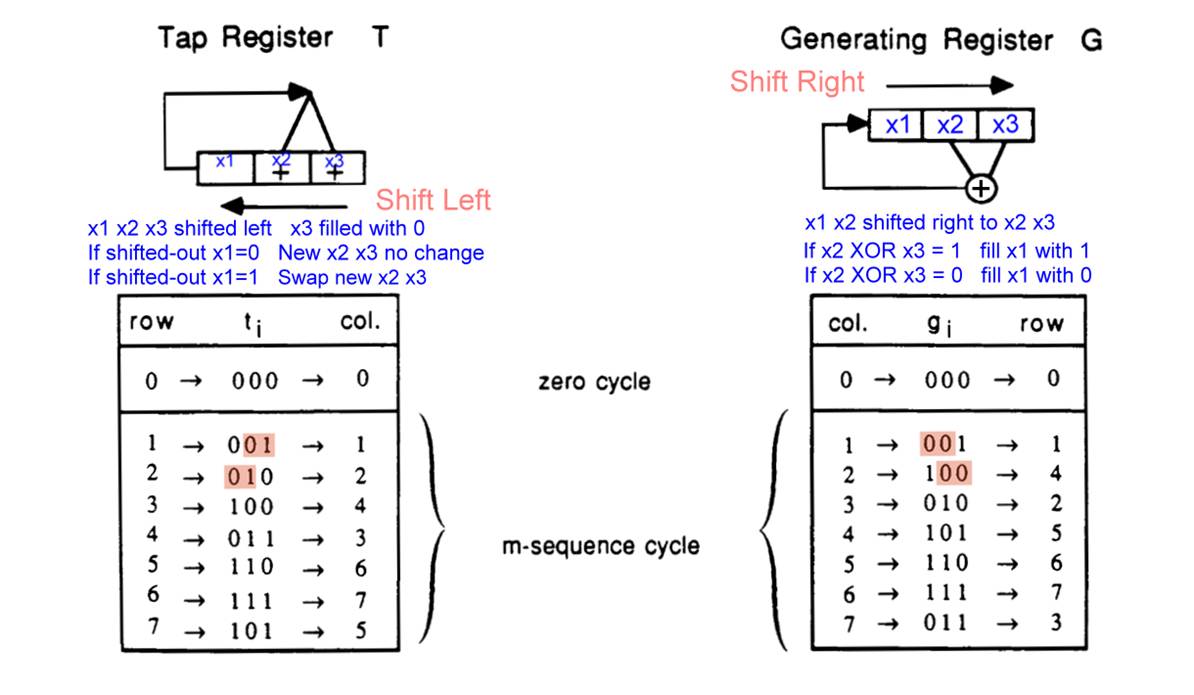

How to generate M-sequence?

First, let's review binary numbers: 1 (001) 2 (010) 3 (011) 4 (100) 5 (101) 6 (110) 7 (111)

Here, we use the most basic and shortest M-sequence with

n = 3 as an example.

There are two ways of Shift Registers: shift left and

shift right.

The first method (left figure) �V The three positions of

the generating register are designated as x1, x2, and x3.

x2 and x3 are shifted left to x1 and x2, and x3 position

is filled with 0.

If the shifted-out x1 is 0, the 0 or 1 at two right

positions remain unchanged

If the shifted-out x1 is 1, the 0 or 1 at two right

positions are inverted (0 becomes 1, 1 becomes 0) �V in other words, the

generating register contents are XORed with the tap register 3 (011).

Starting from 1 (001), repeat this register shifting

process. The generating register will sequentially become 2 (010), 4 (100), 3

(011), 6 (110), 7 (111), and 5 (101), then return to its starting number of 1

(001).

The sequentially shifted-out 0 or 1 from left side of the

generating register construct [0 0 1 0 1 1 1], which is the M-sequence of

length 23-1=7.

The second method (right figure) �V the three positions of

the generating register are also designated as x1, x2, and x3.

x1 and x2 are shifted right to x2 and x3.

If before the shift, x2 XOR x3 = 1, the x1 position is

filled with 1.

If x2 XOR x3 = 0, the x1 position is filled with 0.

Starting from 1 (001), the register is repeatedly shifted,

the content of the generating register will sequentially go through 4 (100), 2

(010), 5 (101), 6 (110), 7 (111), and 3 (011), before it returns to the

starting number of 1 (001).

The sequence [1 0 0 1 0 1 1] derived from shifted-out 0

or 1 from right side of the generating register is the M-sequence of length 23-1=7.

This

is the BASIC program that generates the M-sequence of n = 7 and tap = 65,

according to the first method:

DEFINT

A-Z

n

= 7

tap

= 65 ��---------------------------------------------------

tap-register = 65 (1000001)

nn = 2 ^ n �V 1

DIM

M(nn) ��------------------------------------------------ Length

of M-sequence 2n-1

M(1) = 1 ��---------------------------------------------------

Starting value = 1

CLS

FOR

i = 1 TO nn

IF M(i) >= 2 ^ (n -

1) THEN ��--------------------------- If 1 is shifted out

PRINT " 1"; ��-------------------------------------------

This bit of the M-sequence is 1

M(i + 1) = ((M(i) - 2 ^ (n - 1)) * 2) XOR tap ��------- Generating

register XOR tap-register (65) to get new generating register

ELSE '-------------------------------------------------------

Otherwise, if 0 is shifted out

PRINT "0"; '-------------------------------------------- This bit in the

M-sequence is 0

M(i + 1) = M(i) * 2 '---------------------------------------

The generating register remains unchanged

END IF

NEXT

END

M-sequence

of length 27 - 1 = 127 is generated:

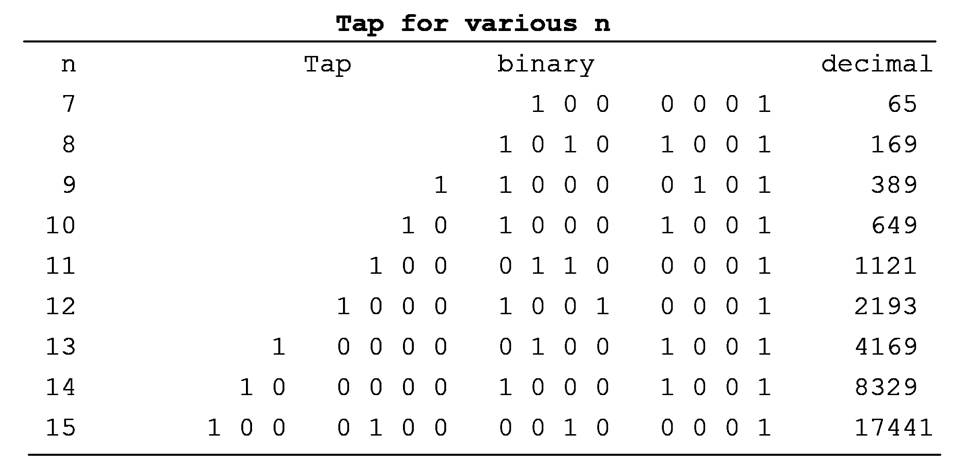

The selection of the tap register is crucial. In the

first method described above, when x1 shifted out is 1, the generating register

is XORed with the tap register to get the new generating register.

A register containing n 0��s or 1��s has 2n

possible arrangement of 0��s and 1��s, which, in binary terms, represent

consecutive integers from 0 to 2n-1.

A poorly selected tap will make the generating register

go back to its starting value too early, not going through all 2n-1

integers. It loops within a smaller cycle without containing all 2n-1

integers. A good tap, on the other hand, the generating register will pass

through all 2n-1 integers (excluding 0) before returning to the

beginning, resulting in a sequence called the ��maximal sequence�� (M-sequence) and possessing some of the special

properties of the M-sequence.

A good tap must have an even number of 1s, but a tap with

an even number of 1s is not necessarily a good tap.

The following

are good taps that would generate M-sequence from n=5 to n=11:

Special Properties of M-Sequence

¨

The most

important property of M-sequence is the method of extracting the responses to

each input. The previous section described the method of extracting responses

with M-sequence of n = 3. Here, we have 8 inputs, stimulated by the same

M-sequence with n = 5, but from different starting points (red arrows) (see

figure). Extracting the response from the summed responses using the -1, 1

sequence corresponding to the 0, 1 of input 1 (see figure) will yield the

response to input 1. This response is an average of 2(n-1) = 24

= 16 responses. Average of m responsses will increase the signal-to-noise ratio

(S/N ratio) by ��m times; here, the

S/N ratio of each responses is increased by 2(n-1)/2 = 24/2

= 22 = 4 times.

[ 1 1

0 1 1

1 1 1

0 1 0

0 0 1

0 0 1

0 1 0

1 ........]

[ 1 1 -1 1

1 1 1

1 -1

¨

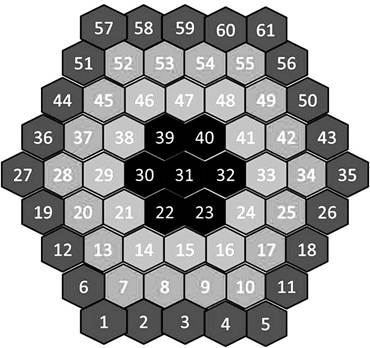

The length of

M-sequence as generated by an

n-bit generating register is 2n-1. It contains 2(n-1) 1��s

and 2(n-1)-1 0��s. In the hexagonal array of a multifocal ERG, if 1

is white and 0 is black, the number of black and white hexagons will always be

approximately equal, and the entire screen will maintain a fixed average

luminance (see figure).

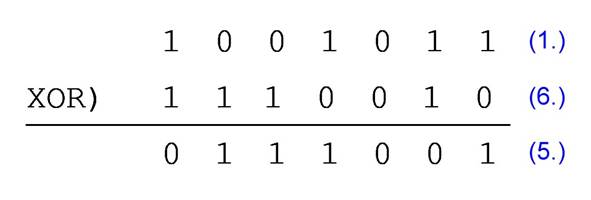

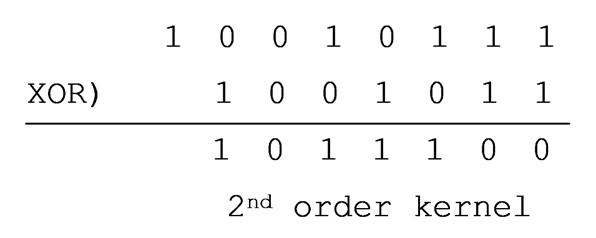

¨

Bit-by-bit XOR

logic operation between any two M-sequences with different starting point among

the 2n-1 M-sequences yields another M-sequence in this group. The

resulting M-sequence is called the 2nd-order kernel, which can be interpreted

as the interaction of the original two M-sequences. However, in jumping into

this interpretation it's crucial to look over the experimental design and the

application of M-sequences to avoid arriving at unforeseen conclusions.

For example, XORing the 1st and 6th M-sequences among a

group of 7 (n=3) M-sequences (left figure) yields the 5th M-sequence (right

figure). Should the response extracted from this 5th M-sequence be interpreted

as a response evoked by the 5th M-sequence stimulus itself, or as an

interaction between the 1st and 6th responses? The solution is to use longer

M-sequences with larger n values to avoid the duplication and confusion.

¨

To achieve good S/N ratio,

multifocal ERG with 241 hexagons needs a long M-sequence. For example,

M-sequence with n=16 contains 216-1 = 65535 0��s and 1��s. Even if

using a computer with 60 displays per second, it would take 65535 / 60 = 1092

seconds = 18 minutes to complete the recording. Nobody would tolerate 18

minutes experiment or examination staring at the computer screen. The recording

is thus broken down into 36 half-minute segments, and the recorded data are

then connected for analysis.

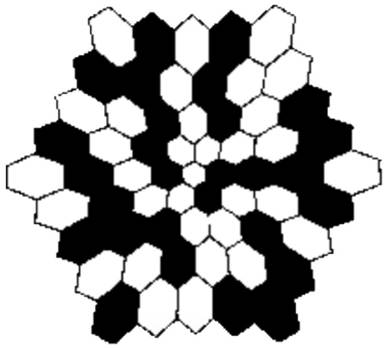

¨

Another example of M-sequence

interaction is the recording of VEP applying M-sequence. Clinical VEP testing

typically uses checkerboard reversal as visual stimulator. Two checkerboards,

checkerboard 1 and checkerboard 2, are regularly reversed at a constant

frequency (left figure). The right figure shows a checkerboard pattern reversed

following an M-sequence �V when the M-sequence is 0, checkerboard 1 is

displayed, and when the M-sequence is 1, checkerboard 2 is displayed.

Checkerboard reversal

regularly Checkerboard reversal

following M-sequence.

¨

Using this M-sequence to extract VEP

from electroencephalogram (EEG) yields a first-order kernel response. There is

no response extracted (left column of right figure). Because the VEP is coming

from the ��reversal�� of the checkerboard, not from the checkerboard itself. To

extract the VEP from the ��reversal��, we must use the M-sequence generated by

XORing two consecutive M-sequences (left figure). This is called a second-order

kernel response. We thus get an NPN waveform similar to

that evoked by traditional checkerboard reversal (right column of right

figure).

If the experimental is designed as swaping the

checkerboards when M-sequence is 1, and keeping the checkerboard unchanged when

it's 0, then VEP will be extracted using the first-order kernel M-sequence.

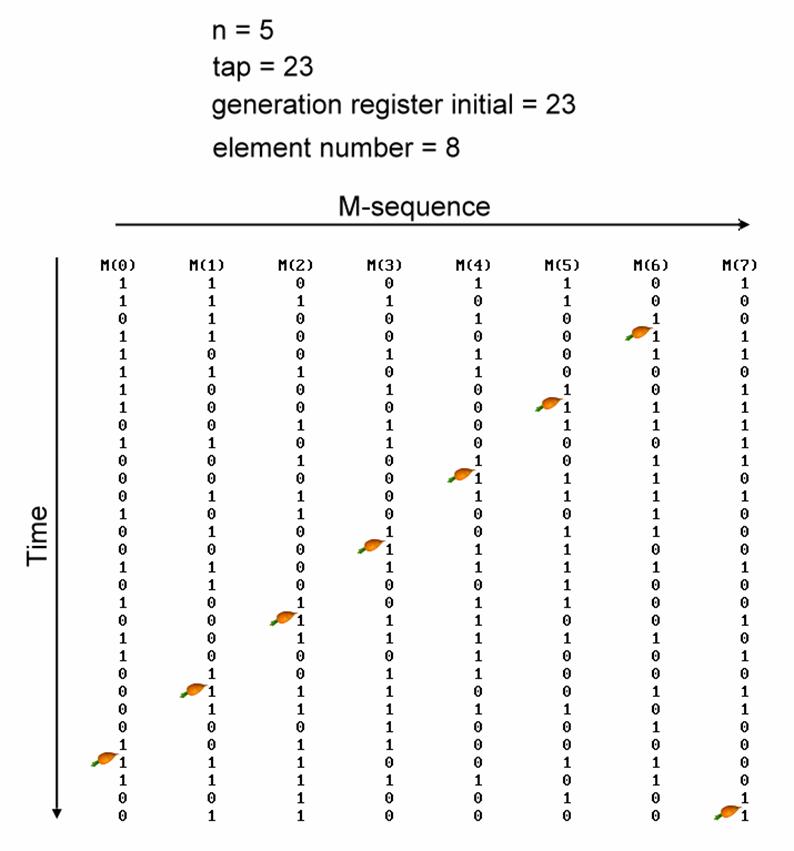

¨

M-sequence can

be real-time generated during experiments, without needing to prepare it

beforehand. For example, with 8 elements, such as a multifocal ERG with 8

spots, at time 1 the 0��s and 1��s of the M-sequence are sequentially assigned to

the 8 elements (see figure, from left to right). At time 2, the sebsequent 0��s

and 1��s along the same M-sequence are assigned to the 8 elements at time 2 (see

figure, from top to bottom), and so on for time 3, time 4, and so on. Once the

2n-1 0��s and 1��s of the M-sequence is used up, the cycle starts

again from the beginning.

With this unique assignment of M-sequence

from left to right and from top to bottom, when a single element is viewed

vertically from top to bottom, it keeps to be the original M-sequence, yet with

different starting point! The start points of M-sequence of these 8 spots is

evenly distributed at positions 1/8 the length of this M-sequence (the red

arrow in the diagram)!

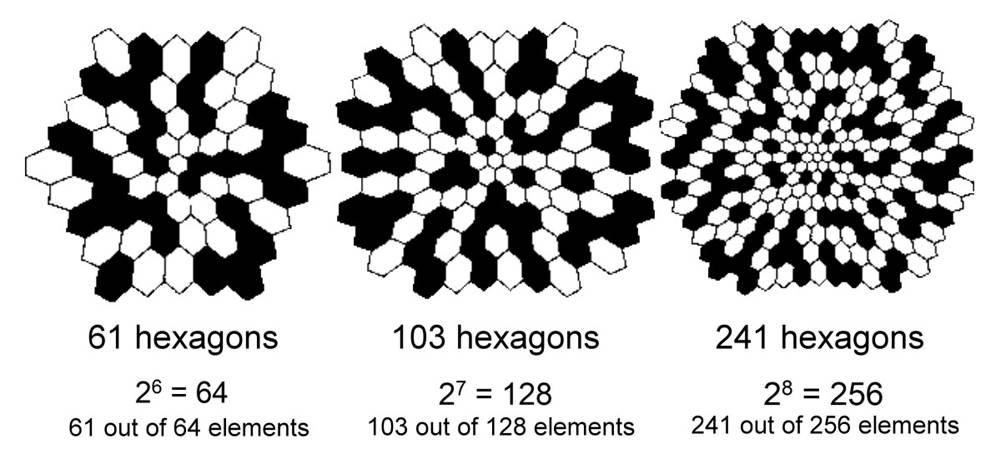

¨

The number of spots

must be a power of 2, such as 1 (20), 2 (21), 4 (22),

..., 256 (28), ..., 2048 (211), 4096 (212) ...

to achieve the aforementioned property of laterally assignment of 0 and 1. The

61 hexagons, 103 hexagons, and 241 hexagons in the multifocal ERG program must

be using 64 (26), 128 (27), and 256 (28) spots

respectively to assign the 0��s and 1��s of the M-sequence (see figure).

¨

This is a

dynamic diagram illustrating the sequential allocation of 0��s and 1��s along an

M-sequence (n=9, length 29-1, tap=33, initial value=67) to 16

elements (see figure, from left to right). After allocating the first 16

elements, the subsequent 0��s and 1��s along the original M-sequence is continued

to be allocated to the second 16 elements (see figure, from top to bottom), and

to the third, the fourth 16 elements, and so on. Once 2n-1 0��s and

1��s of the M-sequence is used up, the loop starts again. With this allocation

of M-sequence from left to right and from top to bottom, when each element is

viewed vertically from top to bottom, it remains to be the original M-sequence,

with different starting point! The starting points of M-sequence of these 16

element are evenly distributed at positions 1/16 of the length of the

M-sequence.

¨

The 61 hexagons

in a multifocal ERG can all be the same size, as shown in the left figure.

However, considering the properties that the central visual field has higher

sensitivity, larger electrical response, and smaller receptive field, the 61

hexagons are designed to be smaller in the center and larger at the periphery

(right figure).

¨

In addition

to generating sequences ��instantly��, the longest sequence can also be analyzed

��instantly�� without needing post-production. The starting points of M-sequences

for these eight elements are known. As the experiment progresses, the

corresponding -1 and 1 sequences for each element are applied to extract the

data. The responses of this element are gradually

averaged and emerge, while the responses of other elements are gradually

cancelled out and diminish. And the responses of each element are gradually

separated and appear. At the end of the experiment, the analysis is already

completed to yield the separate, individual response of each element. This, of

course, requires rapid and large amount computation. Here the Fast

Walsh-Hadamard Transform (FWT)

is the solution.

As mentioned above, the M-sequence can generate

visual stimuli instantly without prior calculation or preparation, the

extraction of responses from each element with M-sequence can also be completed

instantly without post-production. Although this mass computation could be done

by storing EEG and ERG for later processing, if the responses of at least one

element can be presented instantly during the experiment or examination, we

would be able to monitor the whole recording course and detect any error immediately.

For fast, real-time analysis of M-sequences, please refer to Hadamard-Walsh Transform�AFast

Walsh-Hadamard Transform (FWT). It

is a generalized Fourier Transform�AFast Fourier

Transform (FFT). Although

the mathematical operations of these transformations are complicated, the

algorithms are publicly available and not entirely inaccessible.

(The Hadamard transform is also known as the

Walsh�VHadamard transform, Hadamard�VRademacher�VWalsh transform, Walsh transform,

or Walsh�VFourier transform.)

Jacques Solomon Hadamard(1865-1963)�AHans Adolph Rademacher(1892�V1969)�AJoseph Leonard Walsh(1895�V1973)

This is Erich Sutter's system, EDI's VERIS.

Erich Sutter did not apply a patent in Europe.

There��s German company copied the system, the RETI-scan visual

electrophysiology system (Roland GmbH, Germany).

The following visual electrophysiology systems

were showcased:

EDI VERIS (USA),

RETI-scan (Germany),

Diagnosis (USA), and

Metro Vision (France).

At a conference in mainland China, I had seen Chinese

companies also presented their own version of this system.

GT-2000NV (Chongqing Guote

Medical Equipment Co., Ltd.),

BIO-2000 (Nanchang Wufang

Medical Device Co., Ltd.),

IVE-205A (Chongqing Airxi

Medical Equipment Co., Ltd.), and

APS-2000A (Chongqing Kanghua

Technology Co., Ltd.).

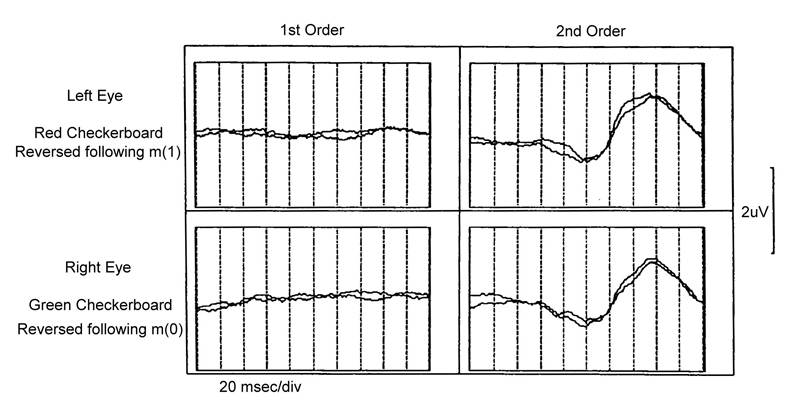

VEP of both eyes recorded simultaneously with

M-sequence

Clinical VEP typically tests each eye

separately. Since the M-sequence is a multiple inputs,

single output system, its characteristics allow for the analysis of individual

response to each input from a single summed output. Therefore, we designed a

computer program to record VEPs of both eyes simultaneously using red and green

glasses �V green for the right eye and red for the left. The red and green

checkerboard reversal follow the 0 and 1 of an

M-sequence. In terms of M-sequence algorithm, this is a much smaller scale than

Erich Sutter's multifocal ERG, using only two elements: the left and right

eyes. The red checkerboard of left eye follows M-sequence M(1) �V checkerboard 1

is displayed when M(1) is 0, and checkerboard 2 is displayed when M(1) is 1;

the green checkerboard of right eye follows M-sequence M(2) �V checkerboard 1 is

displayed when M(2) is 0, and checkerboard 2 is displayed when M(2) is 1. The

left figure shows the conventional black and white checkerboard reversal, and

the right figure shows the red and green checkerboards reversed following the

M-sequence, which records the VEP of both eyes simultaneously.

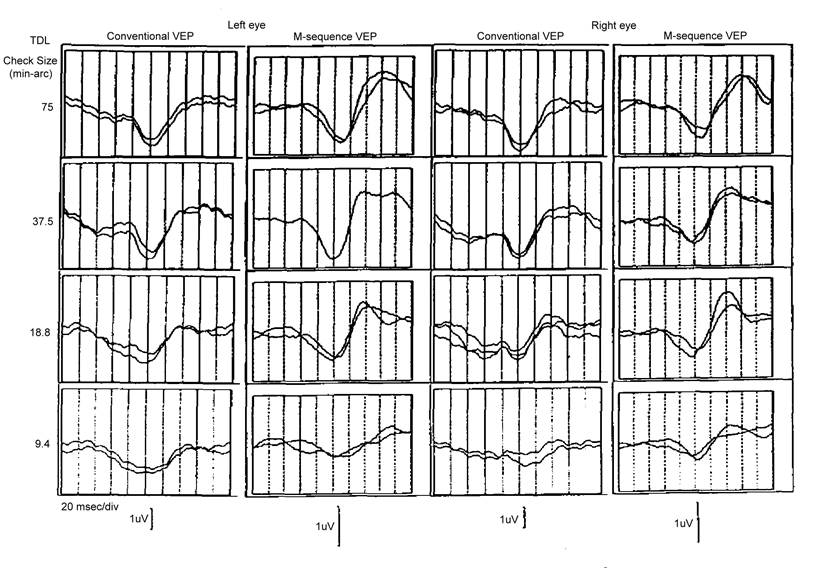

We compared the VEP��s of (1) checkerboard

reversal following M-sequence and (2) the conventional checkerboard reversal at

regular frequency. From top to bottom are 4 successive

half-sized checkerboard (see figure). It can be seen that by recording both eyes simultaneously

based on M-sequence, we obtained almost identical NPN waveforms of pattern VEP.

Conventional VEP

M-seq VEP Conventional VEP M-seq VEP

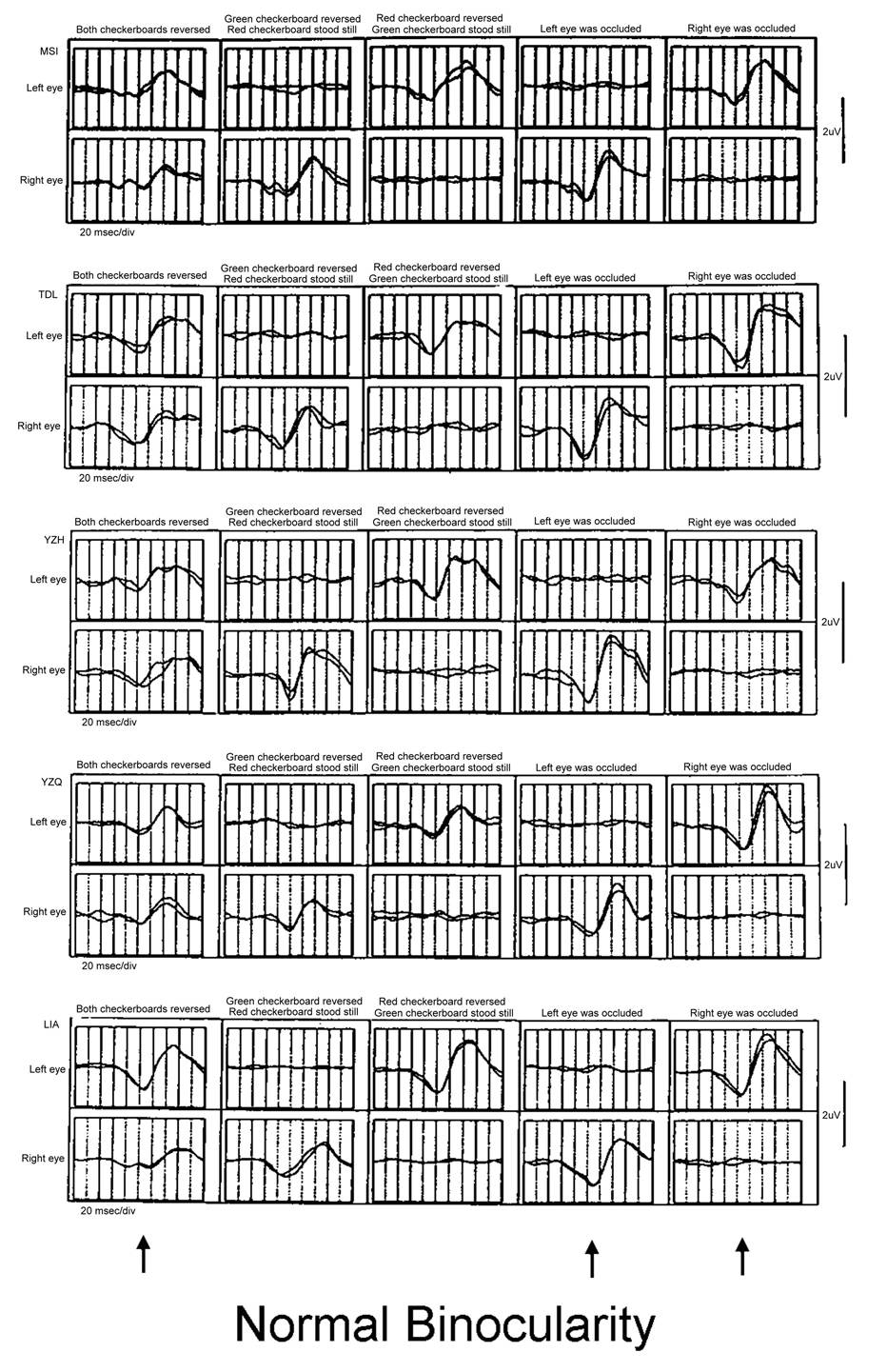

Both eyes recorded simultaneously also allows

us to observe whether there is any interaction between the two eyes. We

recorded five items �V

(1) both eyes looking simultaneously,

(2) the checkerboard viewed by left eye is

stationary,

(3) the checkerboard viewed by right eye is

stationary,

(4) the left eye is covered and only the right eye

views the checkerboard, and

(5) the right eye is covered and only the left

eye views the checkerboard.

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

These are five individuals with normal

binocular vision and stereopsis. The amplitudes of the simultaneous recording

of both eyes with M-sequence (left column) is only half that of one-eye

recording (right two columns).

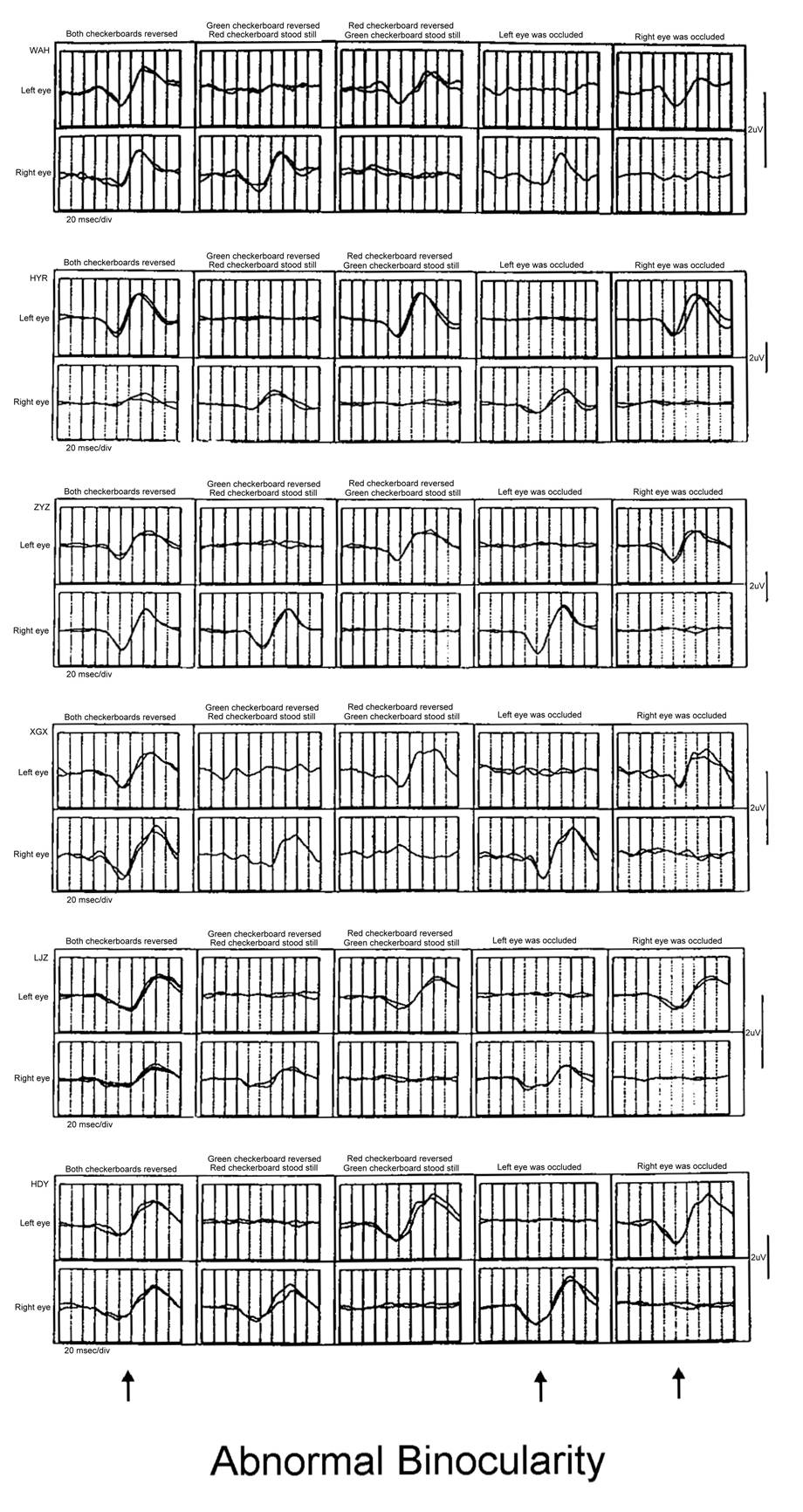

These are six patients with poor binocular

vision who failed the stereopsis test. The amplitudes of the simultaneous

recordings of both eyes with M-sequence (left column) and the amplitudes of the

monocular recordings (right two columns) are almost identical.

Dr. Suzanne McKee coined

the term ��fusional suppression��, which refers to the phenomenon that in

subjects with normal binocular vision, the interaction between two eyes

suppresses the individual activity of each eye. In engineer��s terms, the

interaction between the two eyes diverts some of the energy from monocular

vision to binocular vision, thus reduces the VEP of

either eye when recorded simultaneously. In subjects with poor binocular

vision, however, the energy remains in each eye's individual monocular vision,

and the VEP of either eye as recorded simultaneously do not decrease,

maintaining the same amplitude as in monocular recording.

References for Fusional Suppression:

McKee SP, Harrad RA. Fusional suppression in

normal and stereoanomalous observers. Vis Res. 1993 Aug;33(12):1645-58.

Fu

VL, Norcia

AM, Birch EE. Fusional

Suppression in Accommodative and Infantile Esotropia. Invest Ophthal

& Vis Sci May 2006, Vol.47, 2450. ARVO Annual Meeting

Abstract May 2006.

Birch

EE, Fu

VL, Norcia AM. Fusional

Suppression During Infancy. Invest Ophthal & Vis

Sci May 2006, Vol.47, 2449. ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract May 2006.

The above demonstrates our

use of a small-scale M-sequence algorithm with only two elements to record VEP��s

from both eyes simultaneously. Similar designs would be able to record VEP��s

from the nasal and temporal half visual fields of one eye (2 units)

simultaneously; record VEP��s from the nasal and temporal half visual fields of

both eyes (4 units), and so on. The interaction between the nasal visual fields

(temporal retina, uncrossed optic pathway) is of great interest because the

uncrossed optic pathway is evolutionarily new. In a long history when two eyes

gradually moved from lateral positions to anterior positions of the head,

resulting in partial overlap of the visual fields and the development of

binocular vision. Increasing proportion of uncrossed nerve fibers in the

evolutionary process should be closely related to the mechanism of binocular

vision.

Multifocal ERG and VEP

examinations are somewhat similar to visual field examinations. The latter is a

psychophysical examination in which the subject responds subjectively, while

the former is an objective recording of electric potentials.

Some researchers have ever

recorded multifocal pupillary light reflexes. They tried to isolate the

contribution of each retinal locus to the pupillary light reflex.

Others have tried to

bleach red and green cones with yellow background, then recorded multifocal ERG

of blue cones using dim blue hexagons, to follow up the progression of glaucoma

which damages blue cone more than red and green cone pathways.

In short, free your

imagination and make good use of M-sequence �V a powerful system of multiple

inputs and single output. It can isolate and analyze the response to each

individual input from the summed single output.